For several moments, social media forgot its narcissism. It was like the day Nelson Mandela died. Every feed mourned Johnny Clegg. Across historical divides, people stood together in the realisation that we have all shared a slice of time with someone who achieved something that was out of the range of expectations of the average South African. And he was ours.

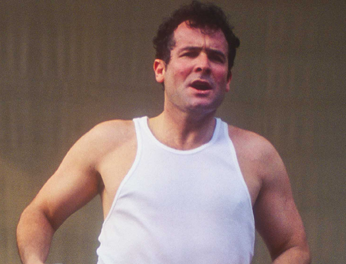

Singer, songwriter, dancer, anthropologist, mensch… Clegg died on 16 July. He was 66 years old.

When the death of a loved one is imminent, loss is a contained idea. Until it happens. Then the fact belies anything that could have been anticipated, as you are left shocked and broken, as though it had come suddenly.

The world knew that Clegg had pancreatic cancer in 2017, when he did his final world tour, making public a private hell that he had been weathering since his diagnosis in 2015.

With his prolific body of songs, his love of culture from the inside out and his ability to blend values into classics, Clegg, who learned and taught social anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand, emphatically redefined popular music, crossing over African music idioms with Western ones. He sold about five million albums over a period of 30 years.

In an interview in 2002, he commented that “uncontrollable passion” is the thing that makes art happen. And he knew this, as a teenager fighting apartheid, an academic and a performer whose Zulu stick-fighting, singing and dancing had surprising and rare authenticity.

From Bacup to Joburg

Born in a small English village called Bacup in Lancashire on 7 June 1953, to a Jewish mother and a Scottish father who subscribed to the Unitarian faith, Clegg travelled with his mother to South Africa when he was a child, making significant pit stops through Africa on the way. From living in Zimbabwe to making wire cars with other nine-year-olds on the edge of Zambia, he grew into a rebellious teenager.

Clegg’s first male role model – his parents separated when he was a toddler – was a Zulu guitarist by the name of Charlie Mzila, who by day was a cleaner in the Yeoville flat where Clegg and his mother lived. At that stage, Clegg was fascinated with Celtic folk music, which reminded him of his father. For him, the Zulu sounds evoked a Celtic 6/8, and with the candour of a 14-year-old, he asked Mzila how he did it. Thus began an important relationship with music, culture and the people of South Africa.

It was 1967. Clegg had come of age and met men who were migrant labourers, visited shebeens and encountered the underbelly of Johannesburg, forbidden to one so young, so white, so middle class. He remembered the first time he encountered the dance:

“There was a single electric light and there was a concrete sports yard, very big, surrounded by buildings … I heard the dance before I saw it … I heard an incredible humming sound … and I saw these 60 or 80 men performing this dance, and I had an overwhelming sense that I was the only young white person who was being exposed to this … I had a sense that the universe was winking at me, saying ‘There’s a very big secret here and it can be yours if you want it.’”

But referring to himself as “no do-goodnik”, he was not anxious about being politically correct. More than anything, Clegg deemed himself “an innocent abroad”. He elaborated in 2002: “I was on a personal journey at the same time I was in the context of a country in massive upheaval.”

In a time when culture was popularly celebrated as a weapon of war, his work was never narrowly political. Of this, he said:

“I managed to keep a semblance of autonomy in my own creative realm. I wasn’t a slavish follower of the latest political decisions. And I think there was a lot of debate about what I was doing. It was stuff which technically wasn’t allowed. Both sides, the government and hard-core politicos, challenged me.”

The best of honours

Clegg was the recipient of many honours, including knighthoods and honorary doctorates. Without being flippant, he brushed their sheen aside. “They’re honours. They don’t add to my career,” he said in 2008. “They acknowledge my journey.”

A more important honour was conferred on him decades earlier, in the 1970s. Wabaleka no Checkers was his Zulu praise name. It means “you ran away with your Checkers bag”. The bag in question had contained his dancing sneakers; he was fleeing an increasingly threatening situation between men who lived in Johannesburg’s mine hostels. At the time stick-fighting contests were increasingly leading to explosive violence. When the situation looked, to Clegg’s teenage perception, to be dire enough, he turned heel and ran for his life. After the confrontation, the image of him fleeing in horror became an affectionate joke between him and his hostel-dweller friends, who fondly bestowed on him the name Wabaleka no Checkers.

After 31 years of marriage, he leaves his wife, Jenny, sons Jesse and Jaron, and devastated fans all over the world. His family will bury him in a private ceremony, with a public memorial to be hosted at a date to be announced.

By: Robyn Sassen